Guide to Intellectual Property and Copyright

** For easier printing and viewing, this guide is available as a PDF .

This guide provides an introduction to Intellectual Property and Copyright for artists, with particular focus on best practices when presenting and sharing works digitally. Intellectual Property law is complex, and this guide does not provide legal advice. Rather, it is intended as a toolkit to support artists when sharing their works online or negotiating the terms of an exhibition with a gallery. It is our hope that by having greater knowledge about their rights under copyright law, artists will feel empowered to determine how their work can be distributed, displayed, and shared, and that establishing these rules at the outset will avoid the need to seek resolution later.

Intellectual Property

The World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO) defines Intellectual Property (IP) as creations of the mind, such as inventions, literary and artistic works, and designs (“WIPO”; Fig. 1). Laws protecting IP balance rights provided to creators over how their creations can be used or shared with the public’s interest in accessing creative and innovative works (Fig. 2). WIPO states that the intent of IP law is to allow creators to benefit financially from their work while fostering an environment in which creativity and innovation can flourish, for the benefit of all (WIPO, “Understanding Copyright”; WIPO, “What is Intellectual Property?”).

IP is generally divided into two branches: industrial property and copyright (Fig. 3). Industrial property includes inventions and designs, while copyright refers to artistic or literary works and, as such, is the focus of this guide.

Copyright

In simplest terms, copyright means “the right to copy” . In practice, though, it is a legal term that is used to describe a set of rights that are provided to the creator of a literary or artistic work under copyright law. Copyright also applies, though sometimes with differing protections, to performances, sound recordings and broadcasts, which fall under Related Rights.

In Canada, a work is protected by copyright the moment it is created and fixed in a material form, as long as it meets the criteria for eligibility under the Copyright Act of Canada

(“A Guide to Copyright”).

Criteria for a work to be copyrightable

To be copyrightable, a work must:

- Be original and unique;

- Not be a copy of a work by another artist;

- Attest to the skill and judgment of its author;

- Show an independent creative effort; and

- Be the personal expression of its author.

In the case of printmaking, photography or sculpture, there may be multiple originals of a single work. When the artist produces, signs, and numbers a limited series, each copy is considered an original work (“Copyright 101”).

Duration of copyright

Copyright protection for a work lasts for the entirety of the artist’s life plus 50 years after their death (Fig. 4). Works that are no longer subject to copyright protection enter the public domain

(“A Guide to Copyright”).

Copyright retention when a work is sold

When an artist sells or gives away one of their works, copyright for the work remains with the artist unless they sign a contract transferring copyright. This means that even after selling an artwork, the artist maintains the right to uses permitted under copyright – such as making reproductions of the work – and that the new owners of the artwork must negotiate uses – such as public exhibitions – with the artist (“Copyright 101”).

Rights protected under Canadian copyright law

Canadian copyright law protects three categories of rights: Economic Rights, Moral Rights, and Exhibition Rights (Fig. 5).

The inclusion of moral rights means that while in Canada we use the term copyright, the protections offered are closer to what some countries term artists’ or authors’ rights, emphasizing that creators have rights in their creations only they can exercise. While economic rights for an artwork can be transferred to another party, moral rights cannot (“WIPO”; WIPO, “Understanding Copyright”).

Economic rights

Economic rights allow the creator of an artistic or literary work to benefit from it financially (Fig. 6). They include:

- The right to produce or reproduce a work in any form;

- The right to perform a work;

- The right to publish a work;

- The right to translate a work; and

- The right to present an artwork in a public exhibition (“Copyright Act”).

Some of these are explained in more detail below. The full list of rights is provided in the Copyright Act of Canada.

Artists may transfer their economic rights in a work to another individual or organization in return for payment. Such payments are often made dependent on actual use of the works and are referred to as copyright royalties. More information is available in our section on Transfer of Copyright.

Rights of Reproduction, Distribution, and Rental

Artists have the right to control the act of reproduction of their work (Fig. 7) – for example, the production of an edition of an artist’s work by a printer. This means they have the right to determine if their work is reproduced, the methods of reproduction, and who is allowed to create the reproduction.

Artists have the right to authorize distribution of their work or copies of it (Fig. 8), meaning they have the right to determine who is allowed to distribute their work and the terms of this distribution. The right of distribution usually terminates upon first sale of a particular physical copy, meaning, for example, that when an artist sells an artwork, the new owner may resell it without the artist’s further permission. However, CARFAC is currently advocating for an Artist's Resale Right that would allow visual artists to receive 5% when their work is resold.

Distribution rights can become more difficult to define and enforce for digital works, and as such the question of applying the right of distribution to digital files is currently being reviewed by numerous legal systems.

Artists have the right to authorize rental of copies of certain categories of work (Fig. 9), such as musical works in sound recordings as well as audio visual works (WIPO, “Understanding Copyright”).

Rights of public performance

A public performance is considered to include any performance of a work at a place where the public is or can be present. The right of public performance entitles the author to authorize live performances of a work, such as a play in a theatre or an orchestra performance of a symphony in a concert hall (WIPO, “Understanding Copyright”).

Translation and adaptation rights

Translating or adapting a work protected by copyright also requires permission from the artist or author. Translation means the expression of a work in a language other than that of the original version (Fig. 10). Adaptation is generally understood as the modification of a work to create another work (Fig. 11).

The right of adaptation has been the subject of significant discussion in recent years due to the greatly increased possibilities for adapting digital works. This discussion has focused on achieving an appropriate balance between an artist’s right to control the integrity of their work and the rights of users to make changes that would be considered part of the normal use of digital works. Some of the questions revolve around whether authorization from the artist is needed for a user to create a new work that use parts of previously existing works, for sampling another artist’s work in a song (WIPO, “Understanding Copyright”). This discussion is continued in our section on Creative Commons.

Moral rights

Unlike the other categories of copyright, moral rights cannot be separated from the artist; they cannot be sold or given away. Even if an artist sells an original work and transfers all other copyrights, they retain their moral rights in the work. However, there have been contractual agreements between Canadian institutions and artists where the artist agrees not to enforce their moral rights, and in this way moral rights have been waived.

The Government of Canada defines three areas of moral rights:

- The right of credit or association (Fig. 12), which guarantees that an artist is always credited for their work in any future presentation of it.

- The right of integrity (Fig. 13), which guarantees that the work shall remain in basically the same state unless the artist changes it. This guarantees that others may not change the work without permission, but it also guarantees that the artist may change their work at any point. This has resulted in rare cases where an artist has come in to change a painting years after a museum has purchased it.

- The right of anonymity or context (Fig. 14), which guarantees that an artist can decide how the work is used or presented even if they no longer own the work. Under this right, artists have taken their work out of exhibitions even when the museum or gallery owned the work. In these cases the artist did not want to be associated with the exhibition (anonymity) or objected to their work being viewed in that environment (context) (”Moral Rights”)

Exhibition rights

Canada is one of the few countries that have incorporated an exhibition right into our Copyright Act. The exhibition right entitles visual artists to receive payment, in the form of copyright royalties, when their work is included in a public exhibition where the gallery receives public funds. The exhibition fee only applies when the artwork shown is not being actively presented for sale. (“CARFAC-RAAV Fee Schedule”)

Copyright royalty rates for exhibitions are most commonly established through the CARFAC fee schedule. Artist fees are one of three main ways through which most artists receive payment for their work (the others being sales of their work and grants). The fee schedule establishes:

- Minimum rates for exhibitions, both physical and digital, as well as for presentation of individual artworks (Section 1; Fig. 15);

- Royalty rates for the reproduction of artwork in non-commercial books, websites, etc. (Section 2; Fig. 16);

- Royalty rates for the reproduction of artwork in commercial books, websites, etc. (Section 3; Fig. 16);

- Fees for professional services, including leading workshops, writing exhibition statements or other documents, and installation (Section 4).

Many arts councils, including SK Arts and the Canada Council for the Arts, require that public galleries pay artist fees at or above CARFAC rates as a condition of their funding (CARFAC rates are considered minimums, and CARFAC encourages artists to ask for more when negotiating their contract with an organization or gallery). As well, Copyright Visual Arts negotiates copyright licenses on behalf of their members, and the rates their members receive are generally slightly higher than CARFAC minimums.

For galleries that do not receive public funding, it is still recommended they pay at or above CARFAC minimums, and these rates can be a good starting point for negotiation for artists. However, these galleries may not be able to pay at CARFAC rates and may propose lower fees, often in the form of honorariums. Similarly, when an artist leads a workshop for a school or other group that doesn’t receive arts funding, payment may be in the form of an honorarium below CARFAC rates for professional services. The reality for emerging artists is that they must often build their reputation and CV through non-funded spaces before receiving exhibitions in galleries that receive SK Arts or Canada Council funding. As a result, while CARFAC fees provide a fee guideline, emerging artists may find themselves negotiating fees outside of this fee schedule. In this case, it’s important to remember that, unless an artist has signed over copyright, no one can exhibit their work without permission, which establishes a clear basis for this negotiation.

Transfer of copyright

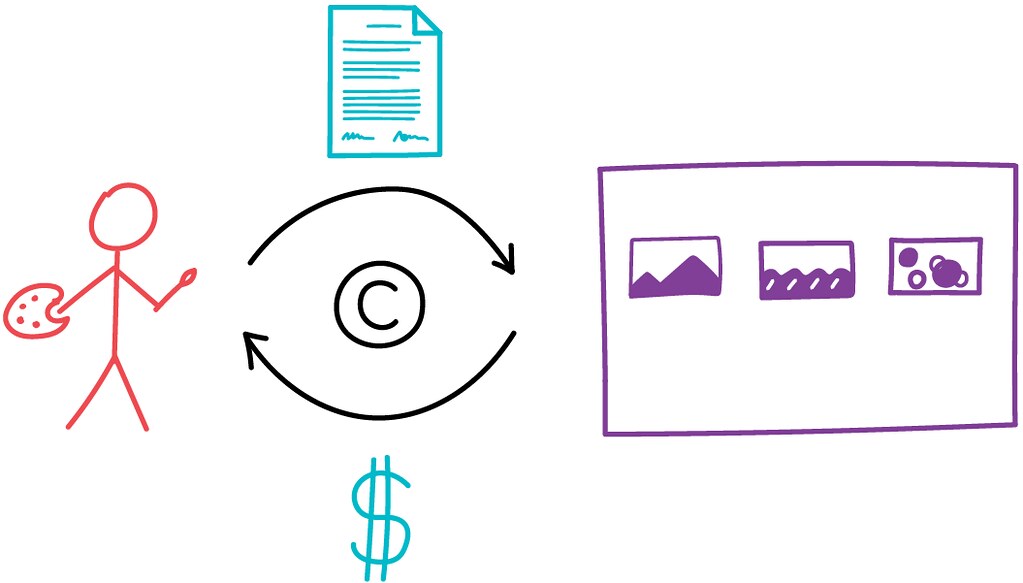

Under Canadian copyright law, the creator of a work may transfer some or all of their economic rights in a work to another party (a museum, art centre, publisher, producer, etc.). This is done by signing a contract which provides certain rights to the user in return for compensation in the form of a copyright royalty which is usually, but not always, monetary (Fig. 17). Generally, artists transfer copyright when they feel other companies or individuals are better able to market and sell their work (“Copyright 101”).

Transfer of copyright may take one of two forms: assignment (which is permanent) and licensing (which is temporary) (“Rights”).

Assignment

An assignment is a permanent transfer of a property right. The person or party to whom the rights are assigned becomes the new copyright owner or rights holder (Fig. 18). Property rights are divisible, so it is possible to have multiple rights owners for the same or different rights in the same work (“Copyright 101”).

Licensing

Licensing means an artist retains ownership of the economic rights in a work but authorizes a third party to carry out certain acts covered by economic rights (Fig. 19), generally for a specific period of time and for a specific purpose. For example, the author of a novel may grant a publisher a license to make and distribute copies of the novel.

Licenses may be:

- Exclusive – the artist agrees not to authorize any other party to carry out the licensed acts; or

- Non-exclusive – the artist may authorize others to carry out the same licensed acts (WIPO, “Understanding Copyright”).

Licensing may also take the form of collective administration of rights, where an artist hires another person or organization to act on their behalf, granting licenses for third-party use of the artist’s work in eschange for royalty payment. This can offer benefits for artists, particularly when digital works are involved, and is discussed further in our section on collective management of rights.

Artists may also choose to make their works available for certain types of sharing and re-use by others for free through open licenses. The most common and widely-accepted are Creative Commons licenses, which are discussed in detail in our section on Open licenses.

Limitations and exceptions to rights

Some uses of an artwork that usually require an artist’s permission may, under certain circumstances, be conducted without it. The two basic types of limitations and exceptions are:

- Free use, which carries no obligation to compensate the artist for the use of their work without permission; and

- Non-voluntary (or compulsory) licenses, which require that compensation be paid to the artist for non-authorized use.

Free use

Examples of free use include:

- Quoting from a protected work, provided that the source of the quotation and the name of the author are mentioned, and that the extent of the quotation is compatible with fair practice;

- Use of work by way of illustration for teaching purposes;

- Use of work for the purpose of news reporting; and

- Adaptation of work for the hearing impaired (Fig. 20).

Non-voluntary licenses

Non-voluntary (or compulsory) licenses allow the use of works in certain circumstances without an artist’s permission, but require that compensation be paid for that use. Non-voluntary licenses are generally created when a new technology for sharing works emerges, and have been explained based on the concern of national legislators that right owners are hindering or might hinder the development of the new technology by refusing to authorize use of their works. Once adopted, these licenses sometimes remain in the law even after the technology has been in place for many years. In some countries, effective alternatives now exist for making works available to the public based on right owners’ permission, including through the collective administration of rights (WIPO, “Understanding Copyright”).

Related rights

Related rights protect the legal interests of those who contribute to making works available to the public or that produce work that does not qualify for protection under the copyright system. Traditionally, related rights have been granted to three categories of beneficiaries:

- Performers;

- Producers of sound recordings; and

- Broadcasting organizations.

Performers have the right to prevent recording, broadcasting and communication to the public of their live performances without their consent, and the right to prevent reproduction of recordings of their performances under certain circumstances. The rights in respect of broadcasting and communication to the public may be in the form of equitable remuneration rather than a right to prevent.

Producers of sound recordings have the right to authorize or prohibit reproduction, importation and distribution of their sound recordings and copies thereof, and the right to equitable remuneration for broadcasting and communication to the public of their sound recordings.

Broadcasting organizations have the right to authorize or prohibit rebroadcasting, recording and reproduction of their broadcasts. (WIPO, “Understanding Copyright”).

Registration of copyright

While it is not required for a copyrightable work to be protected under copyright law, registration of work with the Canadian Intellectual Property Office can be beneficial if an artist chooses to pursue legal means when enforcing copyright of their work for two reasons:

- A registration can be produced in court as evidence to support that copyright exists and that the registrant is the owner of the work.

- If an artist has to enforce their copyright in a lawsuit against an alleged infringer, the copyright registration may be used as evidence against the infringing party that pleads “innocent infringement.” An “innocent infringer” can argue in court that they were unaware of any copyrights in the infringed work due to the lack of registration and courts will generally award lesser penalties if indeed the infringer is found to be an “innocent infringer” (“A Guide to Copyright”).

Enforcement of copyright

As mentioned above, copyright can be enforced by artists through a variety of methods, including civil lawsuits, administrative remedies and criminal prosecution. However, legal and administrative enforcement can be prohibitively expensive, and as such this guide advocates for proactive measures and enforcements that will help artists to establish best practices to protect themselves, hopefully preventing issues before they start and eliminating the need for follow-up action (“Understanding Copyright”).

Two proactive measures are open licenses and collective management of rights.

Public domain

Public domain refers to creative works that are not protected by intellectual property laws such as copyright (“Welcome to the Public Domain”). These works belong to the public, not an individual artist. They can be re-shared, modified, or otherwise used by anyone, free of charge, and do not require permission from the artist/creator. ("About Copyright"). While not required, it is considered best practice to credit the creator of a work in the public domain when re-using it, if the creator is known.

Works can become part of the public domain in a number of ways:

- The copyright has expired (in Canada, a work enters the public domain 50 years after its creator’s death);

- The copyright owner deliberately places it in the public domain, known as “dedication” (Creative Commons’ Public Domain Mark provides one method for an artist to dedicate a work to the public domain); or

- Copyright law does not protect this type of work (“Welcome to the Public Domain”).

WIPO argues that innovation depends on a rich public domain (WIPO, “Intergovernmental Committee”). Indeed, public domain works are freely available for artists to build upon or remix in their own creations. However, it can be difficult to determine whether a work is in the public domain, as a work’s term of copyright often differs depending on its authorship, format, date of publication, and country of origin (Public Domain). The University of British Columbia has created a guide to help determine if a work is in the public domain in Canada.

Open Licenses

While works in the public domain are free of all copyright, open licenses allow artists to permit sharing and re-use of their work on terms of their choosing while still maintaining their copyright in their work. The most common and widely accepted are those administered by Creative Commons, and as such these are the licenses detailed in this guide.

Creative Commons licenses

Creative Commons (CC) licenses are built on copyright and provide a free and simple way for artists to allow others to share and re-use their work while determining the terms of this sharing and re-use. While copyright operates by default under an “all rights reserved” approach, Creative Commons licenses utilize a “some rights reserved” approach. From the re-user’s perspective, the presence of a CC license answers the question, “What can I do with this work?” (Creative Commons, “Unit 3”).

CC offers a total of six licenses. All require that the artist be attributed for their work. In addition, they allow an artist to choose:

- Whether their work can be re-used for commercial purposes

- Whether their work can be adapted

- Whether adaptations need to be licensed under the same terms as the work that has been adapted

CC also provides two public domain tools that allow artists to dedicate artwork to the public domain or for anyone to mark works that are in the public domain.

The three layers of CC licenses

CC licenses are built in three layers, allowing them to be readable by machines and the general public while also being legally enforceable.

The “machine-readable” layer provides metadata that allows websites and digital services to know the terms under which a work is licensed. This permits features from search based on license terms to the selection of a license when uploading a work to sites such as YouTube and Flickr. This means that CC licensed works are more discoverable and allows those looking for source material to more easily find freely available work.

The “human readable” provide a summary of the key license terms in a format understandable by the general public.

The legal code forms the base layer, providing the terms and conditions that are legally enforceable in court (Creative Commons, “Unit 3.1”).

The elements of a CC license

CC licenses contain a combination of 4 elements denoting the different options available to a licensor:

Attribution or BY. This denotes that the user must credit the licensor and provide certain other information, such as where the original work may be found. All CC licenses include this condition.

NonCommercial or NC. This denotes that the work can only be used for noncommercial purposes. Three CC licenses include this restriction.

ShareAlike or SA. This denotes that adaptations of this work must be licensed under the same terms. Two CC licenses include this restriction.

NoDerivatives or ND. This denotes that reusers cannot share adaptations of the work. Two of the CC licenses include this restriction (Creative Commons, “Unit 3.1”).

The CC License suite

CC licenses offer artists a range of options for sharing their work with the public. The licenses combine the four elements detailed above in six configurations to form the CC license suite.

All licenses include the BY condition, requiring the creator be attributed. The licenses vary on whether they allow a work to be used commercially, whether they allow adaptation, and, if they do allow adaptation, on what terms. From least to most restrictive in the freedoms granted re-users, the licenses are:

Attribution license or CC BY

Permits reuse of the work for both commercial and non-commercial purposes. Adaptations are allowed.

Attribution-ShareAlike or BY-SA. Permits reuse of the work for both commercial or non-commercial purposes. Adaptations are allowed only if they are shared under the same or a compatible license. CC’s version of Copy Left.

Attribution-NonCommercial or BY-NC. Permits reuse of the work for non-commercial purposes only. Adaptations are allowed.

Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike or BY-NC-SA. Permits reuse of the for non-commercial purposes only. Adaptations are allowed only if they are shared under the same or a compatible license.

Attribution-NoDerivatives or BY-ND. Permits reuse of the work for non-commercial purposes only. Adaptations are allowed only if they are shared under the same or a compatible license.

Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives or BY-NC-ND. Permits reuse of the for non-commercial purposes only. Only permits use of the work in unadapted form. The most restrictive CC license. (Creative Commons, “Unit 3.3”).

The CC Public Domain Tools

In addition to the CC license suite, Creative Commons offers two public domain tools.

CC0 Public Domain Dedication Tool

Enables creators to dedicate their works to the worldwide public domain to the greatest extent possible.

Public Domain Mark

A label used to mark works known to be free of all copyright restrictions. Unlike CC0, this has no legal effect when applied to a work but rather functions as a label to let users know the work is in the public domain. Often used by museums, libraries, and archives (Creative Commons, “Unit 3.1”).

Exceptions and limitations with CC licensed works

Creative Commons licenses are copyright licenses, meaning they apply when and where copyright applies. This ensures that CC licenses do not restrict works or uses of works that copyright does not restrict. This also means that CC licenses do not reduce, limit, or restrict any rights under exceptions and limitations to copyright, such as fair use, fair dealing, or provisions for people with disabilities. CC licenses also cover other rights closely related to copyright, such as related and neighbouring rights. Under CC terminology, these rights are referred to as Similar Rights. As with copyright, CC license conditions are only applicable when Similar Rights otherwise apply to the work and to the particular reuse made by someone using the CC licensed work. (Creative Commons, “Unit 3.2”).

CC licenses vs. public domain tools

The CC0 Public Domain Dedication Tool employs the same three-layer design of metadata, common deeds, and legal code used by CC licenses. However, in addition it also employs a three-pronged legal approach, as some countries do not allow creators to dedicate their work to the public domain through a waiver or abandonment of their rights. As such, CC0 includes a “fall back” license that allows anyone in the world to do anything with the work unconditionally. And, third, when both the waiver and “fall back” license are not enforceable, CC includes a promise by the person applying CC0 to their work that they will not assert copyright against reusers in a manner that interferes with their stated intention of surrendering all rights in the work. CC0 also covers a few additional rights beyond those covered by the CC licenses, such as non-competition laws.

Unlike CC Licenses and CC0, the Public Domain Mark is not a method for permitting reuse of a work nor for placing a work into the worldwide public domain to the greatest extent possible. Rather, it is a label that is used to mark works known to be free of all copyright restrictions. It has no legal effect but rather informs the public about the public domain status of a work (Creative Commons, “Unit 3.1”).

Other services offered by Creative Commons

Creative Commons (CC) is a global non-profit focused on enabling access to and sharing of artistic works, and while they are best know for their licenses, they also offer other services, including:

- CC Search, which makes openly licensed material easier to discover and use. As it makes use of the Common Crawl dataset, creators do not have to apply to be included (“About CC Search”).

- CC Global Network, which connects advocates, activists, scholars, artists, and users working to strengthen the Commons (the worldwide collection of works that have been shared with an open license) (“About CC Network”).

Collective management of rights

Licensing may also take the form of collective management, where an artist authorizes a Collective Management Organization (CMO) to manage rights on their behalf. A CMO may grant permission to use the artist’s work, set the conditions for that use, collect and distribute payment, prevent and detect infringement of the artist’s rights, and seek remedies for infringement.

CMOs can offer advantages to artists, particularly when digital works are involved, as these works offer the potential for large-scale distribution in return for copyright royalties, but the administrative time involved to coordinate this distribution can place a burden on artists (WIPO, “Understanding Copyright”).

CMOs administer the rights of multiple artists within specific disciplines and are generally non-profit organizations. Two representing the rights of artists in Canada are Copyright Visual Arts and Access Copyright (“Collective Societies”).

Access Copyright

Access Copyright is a national, non-profit organization that is a collective voice of creators and publishers in Canada. They represent tens of thousands of Canadian writers, visual artists, publishers, and their works, licensing the copying of these works to educational institutions, businesses, governments, and others on behalf of the works’ creators or copyright holders (“About Access Copyright”).

Copyright Visual Arts

Copyright Visual Arts is a non-profit copyright management society, providing artists’ rights administration for nearly 1000 Canadian and Québécois visual and media artists. They negotiate the terms of use of their members’ works, allowing institutions, businesses, and individuals to use these works in exchange for the payment of copyright royalties, which Copyright Visual Arts collects and pays out to the artists (“Who We Are”).

Other Canadian supports for artists

Imprimo

Imprimo is a digital tool that establishes, through blockchain technology, a reliable, clear and transparent connection between an artistic work, its creator, and other rights owners. Imprimo creates a verified record of creation and ownership for artworks so that artists can be properly credited and fairly compensated. By registering their work on Imprimo, artists establish a clear path of ownership for their pieces so that they can protect and monetize their work. Galleries, collectors and others in the art world can access and utilize the data on Imprimo to know exactly who owns the works they deal with.

Imprimo is being developed by Prescient, the creator-focused innovation lab of Access Copyright. It is dedicated to exploring the future of rights management and content monetization. According to their website, they are one of the few organizations globally focused on exploring blockchain and exponential technologies from the creator’s perspective. Imprimo is being developed in collaboration with three national artist rights organizations – CARFAC, Copyright Visual Arts, and Regroupement des artistes en arts visuels du Quebec (RAAV), all of whom have established records in the visual arts and rightsholder communities (“Canadian Blockchain Innovation”).

Artists and organizations can register artworks through Imprimo.

CARFAC

Canadian Artists’ Representation/Le Front des artistes canadiens (CARFAC) is the national voice of Canada’s professional visual artists. As a non-profit association and a National Art Service Organization, their mandate is to promote the visual arts in Canada, to promote a socio-economic climate that is conducive to the production of visual arts in Canada, and to conduct research and engage in public education for these purposes.

CARFAC was established by artists in 1968 and has been recognized by the Status of the Artist Act. They engage actively in advocacy, lobbying, research and public education on behalf of artists in Canada.

Our provincial chapter, CARFAC SK, is a non-profit organization representing visual artists in Saskatchewan. They work to improve the status and well being of artists through research, programs and services, public education, and advocacy. They believe in the visual arts as a profession and value and respect all artists, their rights, their art forms, and their diversity. Memberships are available at both professional and student rates.

Ethics in relation to copyright and digital art

As stated above, Creative Commons (CC) argues for copyright reform: “Our experience has reinforced our belief that to ensure the maximum benefits to both culture and the economy in this digital age, the scope and shape of copyright law need to be reviewed. However well-crafted a public licensing model may be, it can never fully achieve what a change in the law would do, which means that law reform remains a pressing topic. The public would benefit from more extensive rights to use the full body of human culture and knowledge for the public benefit. CC licenses are not a substitute for users’ rights, and CC supports ongoing efforts to reform copyright law to strengthen users’ rights and expand the public domain” (Copyright Reform).

While copyright laws are needed to protect the rights of artists (and CC clarifies that they are not against copyright), indeed these laws are often built on Western, capitalist, and colonialist traditions. In their introduction to why intellectual property is important, the World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO) first states that "the progress and well-being of humanity rest on its capacity to create and invent new works in the areas of technology and culture" (What is Intellectual Property 3), employing harmful evolutionary arguments that frame progress as always positive. Later in the same paragraph, they argue that "the promotion and protection of intellectual property spurs economic growth, creates new jobs and industries, and enhances the quality and enjoyment of life" (What is Intellectual Property 3), linking intellectual property rights and economic development. Reform needs to take place within the intellectual property system, both to bring Indigenous and other excluded practices into copyright law and to balance creators' rights more equally with the rights of users.

On the other side of this argument, on their page on moral rights the Government of Canada states the need to extend artists' rights through a framework of ethics when working with galleries or other institutions. Here, the balance of power often lies with the organizations rather than the artists. While copyright laws support artist rights in these negotiations, the Government of Canada points out that organizations need to be cognizant of the power imbalances and to consider how best to act in the interests of artists and the public in these situations. They state that they cannot derive any conclusions, as these ethics have not been written into laws, but this discussion provides useful considerations for artists when negotiating their rights through contracts or in other forms. This discussion is included directly below:

“Copyright law defines a minimum of rights, but the cultural community has long considered the social and ethical dimensions of agreements around art works. Some of the reasons for this are practical; museums and galleries want to, in fact need to, maintain good relations with individual artists and the artist community. In practice, dealings between arts organizations and artists often result in the artist receiving more rights, considerations, and privileges than the law requires. On the other hand, it would be worthwhile for the arts community to newly explore questions of trust and ethics in dealing with contemporary and digital artists. Why, for instance, are so many media artists reluctant to give master copies and source code to museums? Are the reasons purely economical, or are museums considered by many artists to be as much a part of the problem as the solution? Though much research remains to be done in the area of copyright and the arts, much more still remains to be done about the invisible forces of ethics and trust in the arts community” (“Moral Rights”).

Works cited

“A guide to copyright.” Canadian Intellectual Property Office. www.ic.gc.ca/eic/site/cipointernet-internetopic.nsf/eng/h_wr02281.html. Accessed 14 May 2021.

“About Access Copyright.” Access Copyright, www.accesscopyright.ca/about-us. Accessed 21 May 2021.

"About CARFAC." CARFAC, www.carfac.ca/about/. Accessed 19 Aug. 2020.

“About CC Network.” Creative Commons, network.creativecommons.org/about. Accessed 21 May 2021. Licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 license.

“About CC Search.” Creative Commons, search.creativecommons.org/about. Accessed 21 May 2021. Licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 license.

“About Copyright.” Innovation, Science and Economic Development Canada, www.ic.gc.ca/eic/site/icgc.nsf/eng/07415.html. Accessed 21 May 2021.

“Canadian Blockchain Innovation Will Benefit Visual Artists.” Access Copyright, www.accesscopyright.ca/media/announcements/canadian-blockchain-innovation-will-benefit-visual-artists. Accessed 18 Aug. 2020.

"CARFAC-RAAV Minimum Recommended Fee Schedule." CARFAC, www.carfac.ca/tools/fees/. Accessed 19 Aug. 2020.

“Collective Societies.” Copyright Board Canada. cb-cda.gc.ca/en/copyright-information/collective-societies. Accessed 21 May 2021.

Creative Commons. Creative Commons. creativecommons.org/. Accessed 15 Sep. 2020. Licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 license.

Creative Commons. “Unit 3: Anatomy of a CC License.” Creative Commons Certificate for Educators, Academic Librarians and GLAM. certificates.creativecommons.org/cccertedu/chapter/3-anatomy-of-a-cc-license. Accessed 8 Feb. 2021. Licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 license.

Creative Commons. “Unit 3.1: License Design and Terminology.” Creative Commons Certificate for Educators, Academic Librarians and GLAM. certificates.creativecommons.org/cccertedu/chapter/3-1-license-design-and-terminology. Accessed 8 Feb. 2021. Licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 license.

Creative Commons. “Unit 3.2: License Scope.” Creative Commons Certificate for Educators, Academic Librarians and GLAM. certificates.creativecommons.org/cccertedu/chapter/3-2-license-scope. Accessed 8 Feb. 2021. Licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 license.

Creative Commons. “Unit 3.3: License Types.” Creative Commons Certificate for Educators, Academic Librarians and GLAM. certificates.creativecommons.org/cccertedu/chapter/3-3-license-types. Accessed 8 Feb. 2021. Licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 license.

"Copyright Act." Government of Canada: Justice Laws Website, laws-lois.justice.gc.ca/eng/acts/C-42/. Accessed 24 Aug. 2020.

"Copyright Reform." Creative Commons, creativecommons.org/about/program-areas/policy-advocacy-copyright-reform/reform. Accessed 16 Sep. 2020. Licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 license.

"Copyright 101." Copyright Visual Arts, www.cova-daav.ca/en/droitsauteur-101. Accessed 18 Aug. 2020.

Harris, Lesley Ellen. Canadian Copyright Law. 4th ed., Wiley, 2014.

"Know Your Copyrights." CARFAC, www.carfac.ca/tools/know-your-copyrights/. Accessed 19 Aug. 2020.

Imprimo: A digital fingerprint for visual art. Imprimo, imprimo.ca. Accessed 21 Sep. 2020.

"Moral Rights." Government of Canada: Canadian Heritage Information Network, www.canada.ca/en/heritage-information-network/services/intellectual-property-copyright/nailing-down-bits/moral-rights.html. Accessed 24 Aug. 2020.

“Public Domain.” University of British Columbia, copyright.ubc.ca/public-domain. Accessed 21 May 2021. Licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

"Rights." University of Saskatchewan: University Library, library.usask.ca/copyright/authors-and-creators/rights.php. Accessed 14 Aug. 2020. Licensed under a under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 2.5 Canada License.

"Status of the Artist Act." Government of Canada: Justice Laws Website, laws-lois.justice.gc.ca/eng/acts/S-19.6/page-1.html. Accessed 19 Aug 2020.

"The Artist's Resale Right." CARFAC, www.carfac.ca/campaigns/artists-resale-right/. Accessed 14 Sep. 2020.

Vollmer, Timothy. "Supporting Copyright Reform." Creative Commons, 16 Oct. 2013, creativecommons.org/2013/10/16/supporting-copyright-reform/. Accessed 16 Sep. 2020. Licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 license.

“Welcome to the Public Domain.” Stanford Libraries, fairuse.stanford.edu/overview/public-domain/welcome/. Accessed 20 May 2021. Licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial 3.0 United States license.

"Who We Are." Copyright Visual Arts, www.cova-daav.ca/en/About. Accessed 19 Aug. 2020.

"WIPO." World Intellectual Property Organization. www.wipo.int/portal/en/index.html. Accessed 11 Sep. 2020. Licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 IGO license.

World Intellectual Property Organization. “Intergovernmental Committee on Intellectual Property and Genetic Resources, Traditional Knowledge and Folklore.” Seventeenth Session, 30 Sep. 2010. www.wipo.int/edocs/mdocs/tk/en/wipo_grtkf_ic_17/wipo_grtkf_ic_17_inf_2.pdf. Accessed 21 May 2021.

World Intellectual Property Organization. “What is Intellectual Property?” WIPO Publication No. 450(E), doi:10.34667/tind.28588. Accessed 11 Sep. 2020. Licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 IGO license.

World Intellectual Property Organization. “Understanding Copyright and Related Rights.” WIPO Publication No. 909E, doi: 10.34667/tind.28946. Accessed 11 Sep. 2020. Licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 IGO license.

This guide is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 2.5 Canada Licence (CC BY-NC-SA 2.5 CA) unless otherwise noted.

Shared Spaces is a three-year project of the University of Saskatchewan Art Galleries & Collection exploring how Augmented Reality (AR) can create opportunities for connection through art. We acknowledge the support of the Canada Council for the Arts.